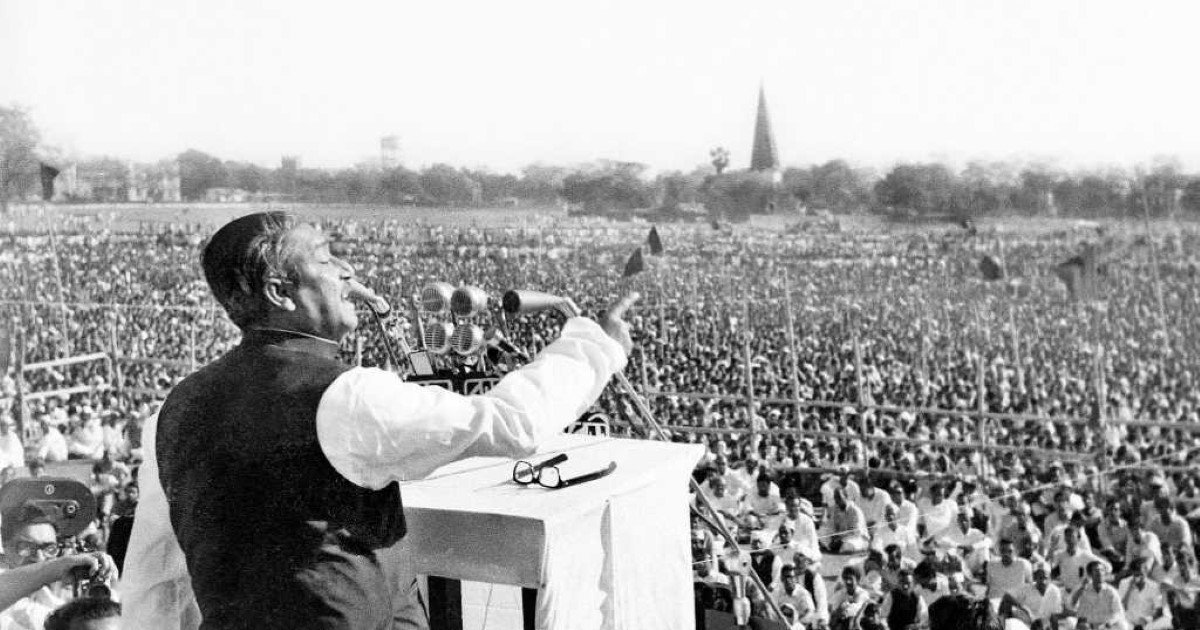

Today’s leaders frequently employ teleprompters, which show text onto translucent beam-splitter mirrors to give the impression that their statements are unscripted and unplanned. Bangabandhu had a teleprompter too, but instead of using pixels for his characters, real people were seated in front of him. The words and the world of his speech were his people in the audience. On March 7, 1971, they materialized in millions on the grounds of what is now known as Suhrawardy Udyan, like words on a page waiting for the talismanic touch that would bring words to life. Theirs was the fervor and intensity conveyed by a single leader’s voice.

A nation went on the march on March 7, 1971, following Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s momentous address.

Bangabandhu gave his compatriots 18 minutes to get ready for the last battle they would have to fight for their freedom. He carefully considered every word he spoke, aware that a single misstep would paint him in the international spotlight as a separatist and allow Pakistan’s cunning leaders to completely disregard any chance of a democratic process. Bangabandhu would have no effect from the overwhelming victory in the 1970 general election that gave him the people’s approval to form the government in Pakistan; instead, his opponents could paint him as a “rebel rouser,” as Bhutto put it, and demand that quick military action be taken.

Knowing that the one million people seated in front of him had had enough of the persecution at the hands of the authorities of West Pakistan, he carefully considered every word he spoke. They were prepared to take action because they were enraged by the colonialism and frustrated by the machinations of the West Pakistani authorities. Bangabandhu appeared to be the only one who could see the invisible teleprompter since he was able to read the words and the surroundings in front of him.His friends had warned him, prior to the rally, of the mob sentiment that would not be subdued without a unilateral proclamation of independence.

In the first general elections after Pakistan’s independence in 1947, the Awami League secured an absolute majority of 160 seats, while its opponent, the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), managed only 81 seats. Pakistan’s next prime minister was supposed to be Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. However, the PPP Chairman Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and the military dictator Gen. Yahya Khan did not want an East Pakistani party leading the federal government, hence the National Assembly was not formally inaugurated. Not to add, the wealthy Pakistani nobility showed little to no regard for a man of the people leading them.

The instability in East Pakistan became a worldwide issue due to the strategic interest of the US and China in the country as well as the close relationship between the Soviet Union and India. The world press took notice of Sheikh Mujib’s remarks and conjectured that he would unilaterally declare his independence from Pakistan. But Bangabandhu knew that similar proclamations had failed in Nigeria and Rhodesia.

That is why Bangabandhu found himself at a turning point in history on March 7, 1971. His situation was comparable to that of notable orators such as Nelson Mandela, Winston Churchill, Martin Luther King Jr., and Abraham Lincoln. Great statements like this have historical roots because they preserve the memory of human events. They belong to all of humanity, not just one particular moment in time. It makes sense that in 2017, Unesco designated the speech as a piece of world documentary heritage. In a video message, former Unesco president Irina Bokova praised the people of Bangladesh for being included into the Unesco Memory of the World record for the first time, citing Bangabandhu’s speech as the reason for the honor.

That is why Bangabandhu found himself at a turning point in history on March 7, 1971. His situation was comparable to that of notable orators such as Nelson Mandela, Winston Churchill, Martin Luther King Jr., and Abraham Lincoln. Great statements like this have historical roots because they preserve the memory of human events. They belong to all of humanity, not just one particular moment in time. It makes sense that in 2017, Unesco designated the speech as a piece of world documentary heritage. In a video message, former Unesco president Irina Bokova praised the people of Bangladesh for being included into the Unesco Memory of the World record for the first time, citing Bangabandhu’s speech as the reason for the honor.

A close examination of the text reveals Bangabandhu’s usage of formal and informal registers in addition to tonal rises and falls to persuade and win over his intended audience. Saying, “You know it all,” he gave his audience a sense of empowerment. You’re aware of everything.” He immediately established a familiarity with the folks by doing this. Before offering a prognosis, he diagnoses the societal ailment that affects his people, giving the impression of a compassionate healer. His demands demonstrated how eager he was to maintain the democratic process.

He listed four requirements in order to become a member of the National Assembly: i) martial law to be lifted immediately; ii) all military personnel to be immediately withdrawn to their barracks; iii) power to be immediately transferred to elected representatives; and iv) a proper investigation into the number of people killed during the fighting.

In addition, he threatened to use force against his opponents if his demands were not fulfilled. Significantly, he declared the province to be the center of a movement of civil disobedience, asking “every house to turn into a fortress.” With the renowned proclamation, “The struggle this time is a struggle for our liberty,” he concluded his address. This time, the conflict is over our independence.”

“We kept looking, but the cunning Sheikh Mujib got away with declaring independence,” the Pakistani secret agency reported to the headquarters. Why Bangabandhu chose not to issue a unilateral proclamation of independence on March 7 has drawn a lot of attention. In 1971, Major Siddiq Salik, who was assigned to oversee Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) in Dhaka, provided three justifications: i) Yahya asked Sheikh Mujib not to continue the conversation regarding the National Assembly; ii) The US ambassador to Pakistan at the time paid him a visit the day before, emphasizing that he would receive no assistance from them; and iii) A Pakistani general threatened to use all of his military power to “kill the traitors and raze Dhaka to the ground.”

Bangabandhu refused to give in to coercion. When deciding what to do, he focused on his own convictions.

Close associates of Bangabandhu have all attested to his unusually subdued demeanor prior to the speech. He was thoughtful and at ease. He was consoled by his wife, who said, “You say what you believe in.” He instructed his chauffeur to take a different route from his Dhanmondi home to the Race Course field when traveling to the event. “Do you know what you will be saying today?” inquired the driver. The response from Bangabandhu was, “I will say whatever Allah makes me say.”

“I shall free the people of the land, Insha’Allah,” he continued.